|

|

|

YOU ARE HERE:>>Real or Fake>>Fake Egptian>>Fake scarabs

This article in Italian was drawn to our attention by attalos. Thanks!

It is from Archeogate an Italian academic website.

There are a couple of other interesting articles on scarabs there by the same author, Franco Magnarini.

Thanks to Prof. Alessandro Roccati the director of Archaeogate for permission to place this translated version here.

(Archaeogate was a very interesting a portal for Italian archaeologists which also published preliminary reports of Italian excavations.

Most of the contents were in Italian but many were in English and very useful to an international audience. Sadly this website closed down several years ago)

FALSE SCARABS ON THE MARKET

By Franco Magnarini

Translation by Marco Perale

As with everything on the antiquities market, egyptian scarab seals -]"which are the most common production of Egyptian art", as Petrie defines them (1) - are not exempt from forgery

It's an old problem as the market in these little objects has been flourishing for a long time, due both to the huge number of finds and the low cost that European tourists were charged, from the first three decades of Nineteenth century and the first three decades of the last century. If Flinders Petrie said that during his first Egyptian journeys he used to buy some hundreds of royal name scarabs every year, later on limiting himself to a more selective choice of about thirty (2), and that in Memphis they were found by the hundreds each year and that they ended up in Cairo shops (3), and that Newberry could write that "the soil of Egypt literally teems with them" (4), it's easy to understand the vaste size of this market.

Someone has suggested that the percentage of false scarabs present today in museum and private collections can be not lower than 1 or 2 %, and this probably still is a low estimate.

It's necessary to offer a general premise: don't consider every scarab you have never seen before, either bearing unusual features or strange looking or out of our usual schemes, a fake.

A couple of examples can easily clarify this.

For a long time I considered with suspicion the specimen shown below.

Recently I found documentation (5) of an very similar scarab discovered in the ruins of Ramses's III temple in Luxor. It still is possibile to say that while the excavated scarab is authentic, the example show may be false, but it is hard to believe that a faker would waste his time to forge a specimen that, after all, does not show any particular beauty or attraction at all.

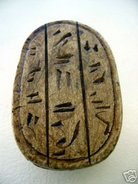

Again, regarding a group of similar scarabs, and among them the example on the right here, I could only finally overcome any doubt I had about their authenticity only when I learned that they were the product of some Greek colonies settled on the northern coast of the Black Sea, at Panticapeum and Bakhchisarai, in Crimea, starting from the VI century B.C. (6). For comparison with number 3, almost identical in shape and form, see the note n. (7).

When an archaeological find spot is not exactly known, which means about almost all of the specimens on the market, it is quite difficult to determine fakery with an absolute degree of certainty. This is especially true when dealing with some extraordinary forgeries produced in the second half of the 19th century. As T. G. Wakelin writes: "it is now extremely

difficult for even well-known Egyptologists to give a definite statement concerning the genuineness or otherwise of a specimen submitted to them" (8). It's also hard to distinguish between the inauthentic and the truly ancient but roughly done specimens made by non Egyptian craftsmen imitating and often misunderstanding Egyptian iconography (the so called Egyptizing scarabs). Jaeger (9) writes about this.

It is a little less difficult to detect modern made pieces, but always keep in mind that can be useful to retain a little bit of doubt.

With these premisses stated, and not believing that I have the ultimate key to enable anyone to point with absolute certainty to a false scarab, it's possibile to offer some guidelines that every new collector should always consider.

First of all it must be remembered that scarabs were worn, in order to assure their amuletic power to the bearer. This is the reason why they

always show a longitudinal piercing that allowed a thread or something else to be passed through and to fix the scarab. When there is no piercing a warning bell must start ringing. On this point, first of all be sure the hole is not just closed off by some dirt or earth, giving the false impression of not being pierced. Again, when looking through the hole, notice that the piercing is not always straight in the authentic specimens.With the bow drilling tools they had, ancient craftsmen could not pierce the scarab through from only one side and so they did it by drilling

from both sides, and as a result that the two piercings do not always follow the same axis.

About exterior shape, suspicion must be raised if the surface of the base shows any convexity. (Though some Cannanite scarabs have slightly convex bases - Bron)

Usually all scarabs when laid on a plane surface sit perfectly on it .It is not an absolutely discriminating criterion, but besides other suspicious elements, it can help when it comes to judging the authenticity of a scarab.

It's well known that fakers have a tendency to imitate those items likely to offer the best selling price. In the market prices seem to be directly related to dimension (and in my opinion not always correctly: smaller scarabs are rarer and should cost more) and to the fact of whether or not they bear a royal name.

The most important criterion allowing us to detect a false scarab is a careful examination look tof he bottom. It is possibile to find inscriptions, plants and animal figures, human beings or mythical deities, but in every case hieroglyphs and signs must be clearly recognizeable and coherent with the standard Egyptian iconographic repertoire. Just to make the point, if anyone were offered a scarab depicting a gazelle or a lotus flower, it certainly would be worth a careful look, but if the scarab showed a penguin or a blueberry bush......

As always, no rule can be absolute. It's not unusual to find Hyksos scarabs bearing pure fantasy signs. A very common example shows the horizontal bars crossed by four vertical short lines at the second, fourth and sixth place from above, but it is no egyptian sign. It only is the Hyksos interpretation of the correct egyptian "n" sign.

For instance, the blue one above on the left is suspicious because of the way the "Sw" feather is depicted, while the next one is suspicious for the reason that the glyphs are very only superficially incised , although it is possibile to read something like: Ra nb tAwy = Ra, Lord of the two Lands.

On the other hand, "the one below is clearly false, because the signs are far from being indentifiable as hieroglyphs at all.

Because of the extraordinary skills of ancient carvers, some patterns are difficult to reproduce. These two specimens show spiral scrolls and other signs that could hardly be carved by hand in our time: only a modern computer controlled pantograph could do the same job. In this case, the probability that we are in front of two authentic specimens is very high.

With royal names, it's necessary to determine that the way they are written is correct. Nevertheless, there are some graphic variations not necessarily negating the authenticity of the scarabs, such as when finding "Mn-xpr-Ra" written with the euphonic "n" complement in th example below" or with the "nb-tA (wy)" title in the scarab beneath that one.

Another pretty common variation is the hoe sign "mr" written the wrong way round from the correct reading direction; in order to adapt it to the curve of the scarab's oval shape.

Generally these are well documented variations. Moreover, it must be remembered that there are some absolutely genuine scarabs bearing some incised glyphs imitating the name of a Pharaoh , the so called pseudo-royal scarabs. Many catalogs always contain a certain number of them (10) (11).

Useful hints can also come from an examination of the materials in which the scarabs are carved. They are pretty dibverse but well known. Steatite is the most commonly used type of stone, whereas turquoise seal scarabs are

extremely rare, this material being spared for jewellery. Running into such a specimen can be a great bargain. or a big loss, since it is highlyprobabile that it is an imitation.

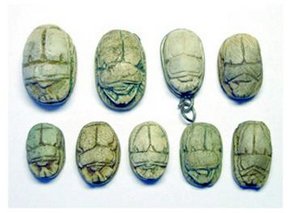

Modern fake scarabs may show the use of hardening resins and moulds. Specimens like the pair below belong to this group.

Besides the material, a close up examination shows that they both come from the same mould; the slight differences are due to tooling which has been used to make them less similar so to obtain yet another "unique" specimen. Moreover, the colour is artificial and made with cold dyes, probably the same as used for glass or ceramics. It must be remembered that in ancient times moulds were also used to produce faience, paste or glas scarabs. But in these cases the decoration, is either clearly impressed or incised. .

Another material used in modern imitations is alabaster, which I suppose was used to obtain the piece below.

The body is quite well carved, but when we take a look at the bottom, the decoration is far away from Egyptian iconography. The first sign from the right is half way between the "Sw" feather (but in this case the reading dierction would show a reverse rendering) and the "i" cane. The second glyph does not either represent the "hrw" hawk, as it was supposedly intended to. The third sign, the first from above, could be the "mn" bilitteral. The fourth seems to be a poorly obtained copy of Gardiner N23 sign. The fifth could be the "nb" basket. The colour too has clearly been created with a`cold dye and later, slightly faded in order to imitate the effects of age, but without succed in obtaining a credible patina.

It is possibile that an authentic specimen, originally not carved on the bottom (12), has had a modern carving added to it . In this case, if the decoration is correctly obtained with the typical "scratch technique" used

during the XII dynasty with hard stone scarabs, it will be very difficult to uncover the fake. It would be necessary to look at the carvings with a microscope, and only if we could find some iron or steel traces in the incisions we would have any certainty, as this metal was still unknown at that time.

At the last step in the value ladder of imitations we can find the rough specimens offered nowadays to tourists. It is necessary to note them for the sake of completeness, but I think that even the most unprepared collector could not be fooled by any of them.

Concluding these concise notes, we have seen that there are many suspicius clues. None of them, when considered on their own can give the certainty . On the other hand, when we have more than one clue in the same specimen, that can be an alarm sign indicating that we might be dealing with a fake and that it is necessary to deepen the critical examination or, if we are a potential buyer, not to regret dropping the supposed bargain.

NOTES

1. Flinders Petrie W.M. "Scarabs and Cylinders with Names" 1917, p.1

2. Flinders Petrie W.M. "Scarabs and Cylinders with Names" 1917, p.1

3. Flinders Petrie W.M. "Button and Design Scarabs" 1925. Reprinted by Aris &

Phillis Ltd Warminster, p. 9

3. Newberry, Percy E. "Scarabs" Archibald Constable & Co. London 1908, p. 2

4. Teeter E.-Wilfong T.G. "Scarabs, Scaraboids, Seals and Seals Impressions

from Medinet Habu" Oriental Institute Publications Chicago Ill. USA 2003, p.

103 n° 164.

5. Hodjash S. "Ancient Egyptian Scarabs a catalogue of seals and scarabs from

museums in Russia, Ukraine, the Caucasus and the Baltic States" Vostochnaya

Literatura, Moscow 1999, p.47 and nrs from 1600 to 1624.

6. Alexeyeva E.M. "Ancient Beads of the Black Sea Area" Academy of Science,

Moscow 1975-1982

Catalogue of exhibition "Art Treasures of Ancient Kuban" Moscow, 1987.

7. http://www.ancienttouch.com/faience.htm - 28.11.03.

8. Wakeling T.G "Forged Egyptian Antiquities" Adam & Charles Black, London

1912.

9. Jaeger, B. "Essai de classification et datation des scarabées Menkheperra"

Editions Universitaires Fribourg CH 1982. § 524.

1o. Jaeger B. "Les scarabées à noms royaux du Museo Civico Archeologico di

Bologna", 1993, nrs. 117-121.

11. Hall, H.R. "Catalogue of Egyptian Scarabs etc. in the British Museum"

Harrison & Sons St Martin Lane London U.K. 1917, ps. 256-260, nrs.

2557-2594.

12. Most examples of Middle Kingdom scarabs in amethyst and cornelian

are uninscribed.

You can purchase a copy of Franco Magnarini's book on his own collection

HERE

HERE

and elsewhere online. Highly recommended!

Other books published by members of this website

Other books published by members of this website

Let us start with the ridiculous.

These are so called scarabs with hieroglyphs frequently purchased by unsuspecting eBayers...

When I say frequently puchased , I mean just that.

The first image is one which has appeared on no less than three different seller's listings in the last 6 months!

The point of showing these strange things is that genuine ancient Egyptian scarabs have genuine ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs incised on them! (Apart form the rare pseudo cartouches and the 15th dynasty "anr" types...and of course the Egyptising Canaanite scarabs and the Mediterranean ones ....but that is relative small print for new collectors)

(In the Middle Kigdom and Hyksos periods (Second Intermediate Period) especailly , there are a lot of well known design elements, but the point it, they are well known!).

These awful fakes are examples of non hierogyphs!

Let us look at the backs of scarabs now.

(It's not all that difficult to learn about the characteristic back designs you know....... get some books! It's all there.

In fact one can tell a great deal by the back design and the sides as well.

With the last one there you might say,"but I've seen that one in a museum"

Ok.

Look at the other side!

Here is a helpful seller of fakes who has given us both sides to look at!

One of the problems with scarabs, for new collectors, and is something which fakers take advantage of , is that the basic shape is pretty simple and easily reproduced. Add to that the fact that each scarab is unique and different, and though there are series which are similar or well nigh identical, the range is really quite vast. Because you have never seen the like before does not mean it's fake.

So what should a new collector do?

Well, apart form buying as many books as he/she can, and getting in touch with people who do know, handling as many genuine scarabs as possibe (through your local friendly dealer.....of you are in London , contact me!) is an exceptionally useful thing to do.

Museums have collections but they are often displayed in such a way that it 's difficult to look at them closely. You really need to handle them and be able to peer at them closely with a x10 and even x 20 loupe, to become familiar with the types of cutting work which are genuine, and the types which definitely are not, and also the range of hieroglyph signs and other motifs.

Learning at least a basic hieroglyph reading is essential, and actually not difficult to achieve and adds enormously to one's enjoyment of these very interesting little masterworks of ancient times. In fact, if you don't achieve at least basic reading of hieroglyphs you will miss the point entirely.

These were not art objects, despite their often great aesthetic appeal, but objects of various and interesting uses in everyday life. They speak eloquently of many intriguing aspects of ancient Egyptian life, thought, belief and custom. They give evidence of trade patterns in the ancient Near East and Mediterranean, demonstrate the ways in which Egyptian thought and iconography in had influences far away in place and time, and not least, provide insights into orgnisational structures and political control and "spin" in ancient Egypt.

You can see, I'm rather fascinted with them! One of the reasons is that though I've collected antiquities for over 45 years, it was only when I started some dealing a few years ago that I really started to look at them properly and think about them; so in many ways I am a new-comer to scarabs and am pleased to be able to share this passion with you.

Another contribution by Franco here; Amunian ![]() cryptographic hieroglyph formulae on scarabs.

cryptographic hieroglyph formulae on scarabs.

And another concening a rare contemporaneous ![]() scarab for Amenhotep I

scarab for Amenhotep I

Go to next page about scarab forgeries

Home | About This Site | Privacy Statement | Gallery | Testimonials | Guarantees

About Collectors' Resources pages | What's New

Search | Site Map | Contact Us